JOHANNESBURG (miningweekly.com) – The burgeoning lithium-ion battery market, buoyed by increased demand for and production of electric vehicles (EVs), among other end-uses, is making it increasingly difficult for producers of tech metals such as lithium and cobalt to keep pace with the demand from technology developers.

Global demand for lithium continues to grow as a result of the manufacture of lithium-ion batteries used to power such devices and, increasingly, EVs predominate in driving demand for the mineral, with lithium cathode equivalent (LCE) demand increasing from about 160 000 t in 2015 to 180 000 t in 2016.

According to data from the US Geological Survey (USGS), lithium global end-use markets are estimated at 35% for battery production, 32% for ceramics and glass products, 9% for lubricating grease, 5% for both air treatment and the production of continuous cast mould flux powders, 4% for polymer production, 1% for aluminium production and 9% for other uses.

BMI Research commodities analyst Molly Shutt and Benchmark Mineral Intelligence MD Simon Moores highlight that demand for lithium continues to be bolstered by the lithium-ion battery and EV markets.

Shutt points out that, globally, sales of alternatively fuelled passenger vehicle are expected to grow at an average yearly rate of 23.5%, accounting for about 22.1% of all new-vehicle sales by 2025.

“We believe that the majority of these sales will be concentrated in developed markets, in addition to China, where significant air pollution and traffic congestion will drive the political will to roll out aggressive subsidy schemes,” she says.

Moores adds that the political will to address pollution issues in China and Western cities will further support consumer demand for EVs and, subsequently, the lithium-ion batteries used to produce them.

However, he notes that the increase in global demand associated with rapid technological innovation has seen physical production of lithium unable to keep pace.

“Lithium is going through the most severe shortage of modern times and with new supply not easy to bring on, this is no doubt set to continue for some years.”

Moores pointed out that US EV manufacturer Tesla’s Gigafactory, in Nevada, in the US, a lithium-ion production facility that is expected to produce EV batteries capable of generating 35 GWh/y of power, is yet to require lithium supply.

The Gigafactory broke ground in June 2014 and is expected to reach full battery production capacity next year.

Moores says, however, that nine of the 14 lithium-ion battery megafactories tracked by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence are being built in China, with more expected to follow in that country.

“While Tesla’s plant was the catalyst and is vitally important to show that the impossible can be done, China’s battery blueprint is going to be much, much larger,” he declares.

According to international trade statistics organisation Trade Map LCE, lithium imports are dominated by South Korea, the US and Japan, with year-on-year imports increasing by 24.8% to 20 100 t, 20.5% to 15 600 t and 31.7% to 15 800 t respectively.

Although no data is currently available for Chinese imports, Shutt presumes that Chinese lithium imports “increased significantly last year” based on increased EV production in China, while Moores adds that lithium is one of the few minerals for which China relies on imports for supply.

Lithium Suppliers

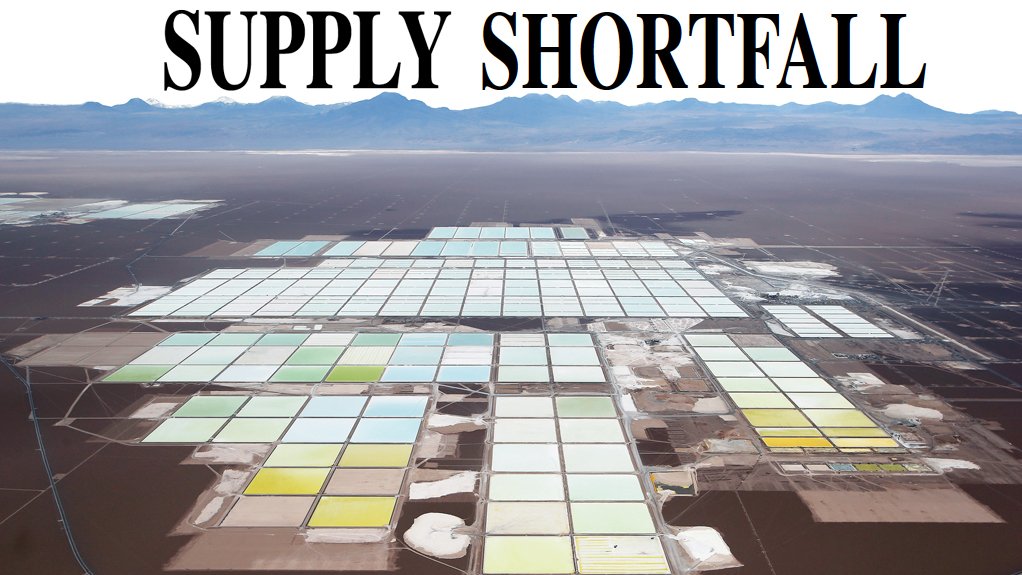

Meanwhile, Shutt notes that Australia, Argentina, Chile and China are the current global leaders in lithium production, accounting for over 95% of global output in 2016. “Our 2017 forecasts for these countries totals over 90 000 t, meaning that global supply will more than double.”

She highlights that global speciality chemicals company Albemarle Corp’s La Negra brine deposit, in Chile, which has received approval for an expansion project in January, is expected to produce 70 000 t/y of technical and battery grade LCE and 6 000 t/y of lithium chloride.

Further, the Cauchari-Olaroz project, valued at between $500-million and $600-million, in Argentina, a 50:50 joint venture between Argentinian producer Lithium Americas and Chilean chemicals producer Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile, known as SQM, boasts expected LCE production of 40 000 t/y once the project reaches full capacity.

However, USGS data suggest that Bolivia holds the largest lithium deposits in the world, with a resource estimate of nine-million tons, with Chile and Argentina holding 7.5-million tons and 6.5-million tons respectively.

Other Tech Metals

Moores tells Mining Weekly that the “profound’ effect that battery cell manufacturing has had on lithium production is expected to have a similar effect on other metals, such as cobalt, graphite and copper, typically used in the production of technology.

He points out that cobalt demand increased significantly last year, owing to increased cathode battery production, resulting in the price of the metal rising 60% over the past 12 months. Cobalt demand for use in battery production increased by 8% in 2016 to about 50 000 t.

There was also a significant increase in demand for graphite anode material, from about 74 000 t to about 100 000 t last year. But, as an industry about three to four times the size of that of lithium, graphite feedstock prices are less sensitive to demand pressures, Moores explains.

He points out that copper demand is also expected to climb on the back of increased EV production and commercial power storage applications, owing to the metal’s use in electricity transference.

“These are new industries that are starting to emerge and causing disruption across the whole supply chain.”

Cobalt Conflict

Human rights organisations Amnesty International and Afrewatch reported last year that some cobalt supplied by China-based Huayou Cobalt, and its Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) subsidiary, Congo Dongfang Mining, had been sourced by child labourers as young as seven years old.

The DRC produces about 60% of the world’s cobalt, which is used in the production of batteries.

The report, titled ‘This is what we die for: Human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of Congo power the global trade in cobalt’, published in January last year, stated that some technology companies, including Apple, Samsung and Sony, had failed “to do basic checks to ensure that cobalt mined by child labourers has not been used in their products”.

The ethical sourcing of conflict minerals, such as cobalt, tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold, have always been a concern for companies, but “the report certainly added more impetus to solving the issue”, Moores highlights.

“While the illegal mining of cobalt, for example, is only a small part of artisanal mining and an even smaller proportion of cobalt mining as a whole, its a stigma for major producers,” he says.

Moores suggests that the best way of ensuring that conflict minerals – so named for their use by groups involved in destabilising entire regions through armed insurgencies, for personal gain – do not enter the supply chain, is for the related mineral industries to solve the problem themselves.

Government policies, such as the US’s Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which require companies to disclose the details of their supply chains in their yearly financial reports, did not have the intended impact.

“If change is really going to come to cobalt, then the cobalt mining industry’s culture needs to change. This is now being led not only by organisations like the Cobalt Development Institute but also major downstream end-users of batteries and components, such as Apple.”

Human Rights Watch business and human rights director Arvind Ganesan confirms that mining revenues from the DRC’s coltan industry that have helped fund armed groups in the country, contribute to “widespread abuses against civilians due to armed groups’ ability to finance themselves through such mining proceeds”.

Policies such as the Dodd-Frank Act aim to cut off funding to such groups by requiring companies to trace and disclose their supply chains.

However, US President Donald Trump has announced his intentions to have the Dodd-Frank legislation repealed, raising serious concerns over the impact this will have on conflict minerals entering global markets.

Ganesan argues that, should the Dodd-Frank Act be repealed, those companies which have invested significantly in removing conflict minerals from their supply chains, as a moral imperative rather than a legal requirement, will be placed at an economic disadvantage, compared with companies that do not want to disclose or eliminate conflict minerals as part of their supply chains. “This could easily create perverse incentives, where responsible companies are disadvantaged,” he warns.

Ganesan suggests, therefore, that progress made in the fight against conflict minerals might be reversed, particularly in the US.

Meanwhile, he notes that several companies, including technology giants Apple and Intel, as well as jewellery franchise Tiffany, have displayed the will to remove conflict minerals from their supply chains.

“For example, Intel has said its goal is to eliminate conflict minerals from its products within a few years. However, the US Government Accountability Office said 67% of companies surveyed were having difficulty identifying conflict minerals in their supply chain, so it is still a major challenge,” Ganesan says.

Global Witness conflict minerals lead Sophia Pickles points out that certain companies within the electronics sector have proven to be the vanguard of responsible minerals supply chains. However, these companies’ competitors “have done little or nothing to ensure their supply chains are responsible”.

She says most firms are still at the early stages of scrutinising their business activities, particularly beyond their first layer of suppliers. “Much of this progress is geographically limited to Central Africa, despite supply chain risks being a global reality,” Pickles adds.

She suggests that responsible mineral sourcing should not be focused on identifying and, subsequently, avoiding conflict areas. “The key for companies is to have the right processes in place . . . to respond responsibly to supply chain risks whenever and wherever they occur.”

Edited by: Creamer Media Reporter

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here