Local legislation, including stringent policy frameworks, continues to prove cumbersome for the South African construction sector, particularly owing to the necessity to conduct socioeconomic- and environmental-impact assessments, as well as obtain approval from the respective government departments, which can be quite time-consuming, says professional services network PwC economic adviser Dr Roelof Botha.

According to organisation for public– private cooperation World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index 2017/18, published last month, South Africa is ranked at 61 out of the 137 economies assessed.

This index presents a framework and a corresponding set of indicators in three categories: basic requirements, which include institutions, infrastructure and the macroeconomic environment; efficiency enhancers, including higher education, the labour market and market size; and business innovation and sophistication factors.

Botha compares the process of constructing an asset to navigating a maze, noting the complicated set of regulations and policies to which one must adhere, which is further often complicated by public- sector incompetence.

Fiscal restraint constitutes another challenge, with the country’s debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio being 50% and destined to rise further, which is indicative of government’s reluctance to spend on the development of infrastructure.

“It’s a pity, because, with infrastructure spend, there is a circular flow of capital back into local labour, equipment and materials.”

RDP Acceleration

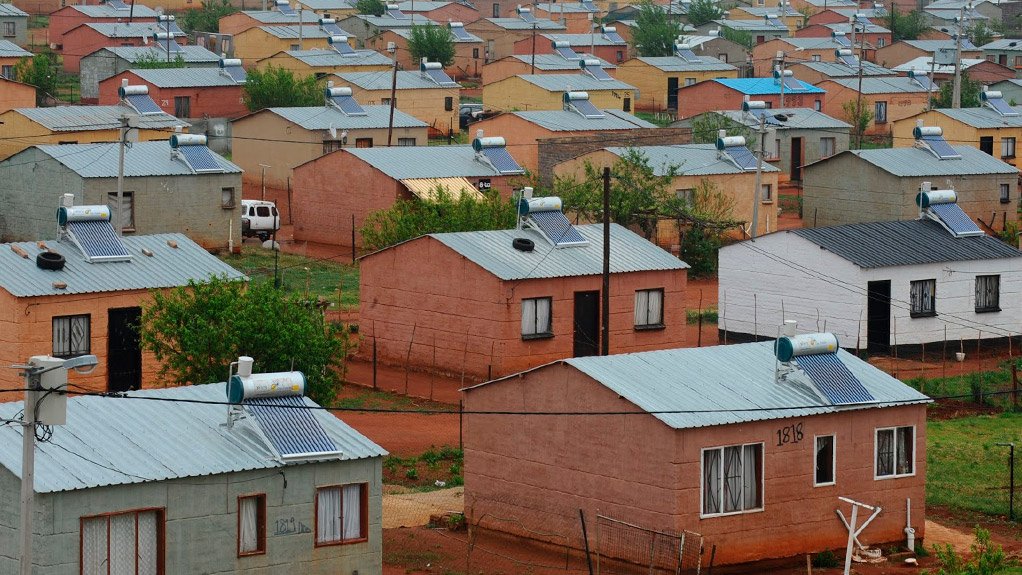

Botha says authorities would do well to accelerate the pace of affordable housing delivery, such as Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) housing.

“RDP housing projects would not only accelerate socioeconomic development during construction but also allow for small enterprise development and an extra taxable income for government, as a result of employment and salaries spent.”

More employment invariably translates into wages spent, the bulk of which should be spent within a municipal jurisdiction, improving the general business climate and the demand for household consumables.

No other key sector of the economy is as labour-intensive as construction, and tenders could also be drafted in such a way that additional points are awarded for methods that create the most jobs, he adds.

Moreover, Botha points out that most of the materials used for RDP housing construction can be sourced locally, which assists with higher value-add in the construction sector’s supply chain.

Botha notes that RDP housing projects will also broaden the property tax base, which will advance the quest for greater fiscal stability.

Banking Trouble

Botha says the South African Reserve Bank’s inflexible approach towards the policy of inflation targeting is costing the economy dearly, which also hinders construction project funding and feasibility.

“There is no doubt that the refusal of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) since mid-2015 to follow an accommodating policy approach as a logical response to the declining trend in the consumer price index (CPI) has contributed to the threat of a return to recession.”

From 2012 to 2015, the Reserve Bank was prepared to allow the repo rate to be marginally lower, on average, than the inflation rate – an obvious response to the weakening economic growth pattern and a conscious effort to prevent South Africa from going into recession again.

“Economists that place a larger premium on a policy mix that is biased towards growth and employment creation have been frustrated since 2015 by the MPC’s adoption of a stringent policy approach, despite the clear absence of any sign of demand inflation in the economy,” notes Botha.

He adds that even ratings agency Moody’s Investors Service has criticised the hiking of interest rates, saying the move was “credit negative” for South African banks.

Reason for Concern

Botha says the Reserve Bank would need to re-evaluate its monetary policy stance – against the background of the producer price index (PPI) having declined by almost 200 basis points from December 2016 to September 2017, without adjusting interest rates accordingly – to preserve economic growth and prevent price instability.

“The PPI is a leading indicator for the CPI, but monetary policy has ignored the fairly predictable downward trend in the PPI that was bound to follow the dramatic decline in the agriculture components of PPI, which constitutes more than a third of the weighting of the total PPI,” he explains.

“Since December 2016, the CPI has declined by 170 basis points and has clearly entered a pronounced downward cycle. The Reserve Bank’s response was lowering the repo rate by a measly 25 points in July – the first decline in the official lending rate in five years.”

Further, Botha notes that inflationary fears emanating from exchange-rate weakness have been exaggerated by the Reserve Bank. The rand regularly recovers from bouts of volatility and was 10% stronger against the US dollar on November 2 than the beginning of last year.

Significantly lower inflation has been on the cards for several quarters and the CPI is bound to continue its downward trend, yet the Reserve Bank seems oblivious of the positive role that lower interest rates could play in lifting the country’s economic growth rate and creating more jobs, Botha concludes.

Edited by: Zandile Mavuso

Creamer Media Senior Deputy Editor: Features

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here