Amid reports that South Africa is attracting less than 1% global exploration spend, Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe has dedicated a national investment of R20-billion to an integrated multi-disciplinary mapping programme to boost global investment in local exploration.

In an address to Parliamentary, in May, Mantashe noted that South Africa hosted 94% of the world’s known platinum-group metals (PGMs) reserves, 73.7% of chrome reserves, 29% of manganese reserves, 18.4% of vanadium reserves and 10.5% of gold reserves. However, the country’s mineral deposits – valued at about $2.5-trillion – have largely gone untouched by local and international explorers and investors, according to a report by independent consultants John Bristow and Dan Moagi that was published by Mining Weekly in March.

“Without modern exploration and prospecting, [as well as] new local and foreign investment, these resources will not be developed . . . and the sector is likely to die out,” stresses Bristow. Mantashe also believes that the country has the potential to supply a big share of global demand for many commodities. He adds, however, that the rich endowment of natural resources and the country’s huge mineral potential can be developed only through a vibrant exploration sector.

To encourage much-needed investment in local exploration, the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) will allocate 51% of its 2018/19 budget to entities reporting to it. Of this amount, 83% will be allocated to companies responsible for critical research and development.

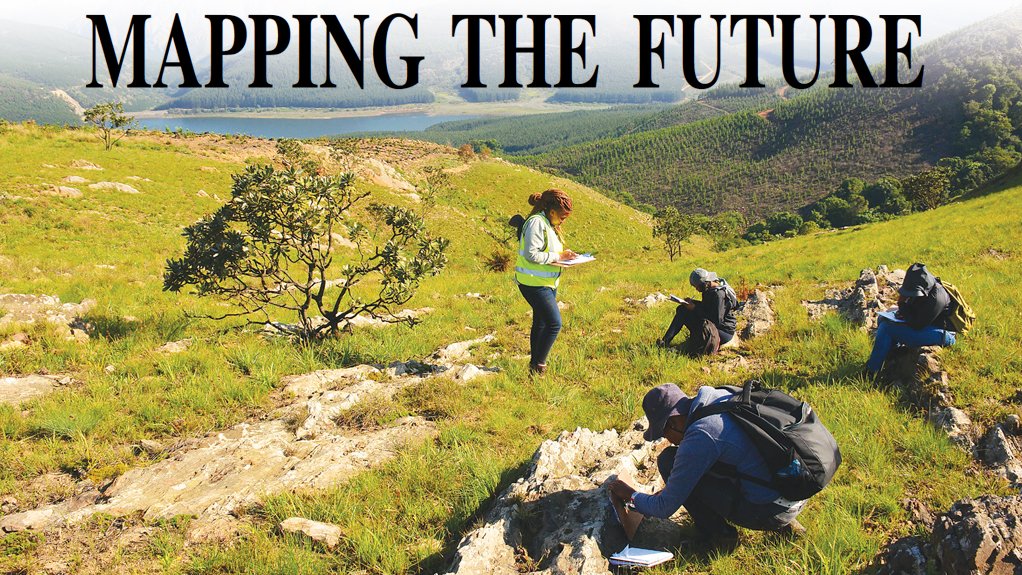

The R20-billion investment announced by Mantashe is expected to be made over the next ten years and will finance an integrated and multidisciplinary mapping programme to be undertaken by the Council for Geoscience (CGS) at a scale of 1:50 000. The programme, which officially began in July, is meant to identify new mineralisation systems – adding to, besides others, the Witwatersrand (Wits) basin (gold), the Bushveld Igneous Complex (PGMs) and the manganese and iron-ore fields of the Northern Cape – as well as other useful resources.

“The programme will assist the country in securing new resources for development, employment creation and economic growth, as well as accelerate transformation,” Mantashe said during his Parliamentary address.

CGS CEO Mosa Mabuza tells Mining Weekly that the council is “hard at work” on the programme and has “a plethora” of geoscientists collecting raw data in several parts of the country for further analysis.

The CGS hopes to publish 40 new in-depth integrated multidisciplinary geoscientific maps for public use by the end of this financial year and intends to have fully mapped 35% to 40% of the country in the next five years.

“It seems like an audacious goal, but, if we hope to complete the programme within ten years, we will have to manage these medium-term commitments,” outlines Mabuza.

He adds that, by modern geological standards, a minimum mapping scale of 1:50 000 is required for a country to be considered an attractive exploration jurisdiction. Thus, the success of the programme is critical to the growth of the local mining and minerals sector.

While South Africa was previously mapped at varying scales of between 1:1 000 000 and 1:250 000, less than 5% of the country has been mapped at the internationally competitive scale of 1:50 000. He avers that the country’s available geological information does not compare favourably with the geological information of other global jurisdictions. The available geological information, he explains, deters potential investors, as it does not contain much detail.

“The CGS began this programme by considering the minimum scale of mapping . . . demanded by explorers and investors. The council’s attention turned to countries that have been able to attract the most investment for exploration and that have the largest share of the global exploration spend,” says Mabuza.

He states that the CGS’s decision to map at a scale of 1: 50 000 was largely guided by the performance of mineral exploration heavyweights such as Canada and Australia, which currently operate at that scale and attract 17% to 18% of global exploration spend each.

“Exploration is . . . a very risky business [and] potential explorers cannot make decisions without comprehensive geological information; South Africa’s geological information is outdated.”

However, Mabuza stresses that the DMR and the CGS hope that the success of the mapping programme will increase South Africa’s share of global exploration spend to 5% in the next five to seven years.

“I truly and wholeheartedly believe that this programme has the potential to rejuvenate our local exploration sector,” he enthuses, adding that the council’s projection of a 5% increase in global exploration spend is conservative.

Consultants and analysts in the local mining and minerals industry have welcomed the investment and Mantashe’s efforts to promote ease of access to critical information. However, many believe the process should have been undertaken years ago and that it will have no notable impact unless it is accompanied by enabling policy. Further, they aver that continuing the preoccupation with Wits gold, PGMs, iron-ore and manganese would be short-sighted.

“South Africa is endowed with a considerable range of other valuable minerals, including modern, high-tech minerals . . . used in batteries, computer chips and lightweight space alloys; hence, the net should be cast much wider,” suggests Bristow.

Advisory firm Eunomix CEO Claude Baissac states: “South Africa has been resting on pseudoknowledge regarding its mineral potential for years.” He explains that, while the industry often attempts to estimate the worth of its mineral endowment, owing to a lack of in-depth geological information, no one in the industry can estimate the figure with certainty. He states, however, that any effort by government and industry stakeholders to improve access to geological information is encouraging.

Bristow affirms that the move towards improving local geological mapping is a crucial step, but hastens to add that the industry should encourage exploration as soon as possible, as the local mining industry cannot hold over exploration for another ten years, and that mapping alone will not solve the problem of a lack of exploration.

Baissac notes that addressing the shortfall in geological information will not be enough to encourage growth in local greenfield exploration.

He maintains that, on its own, the initiative announced by Mantashe will not result in South Africa’s share of global exploration spend increasing, as “up-to-date mapping is just one small piece of the jig-saw puzzle that is holding back exploration”.

Bristow suggests that successful exploration, development and mining require access to real-time information. He says valuable geological information is available in State archives, such as the databases of the CGS, while extensive modern information is in the public domain, including numerous competent person’s reports, technical reports and the bankable feasibility studies of securities exchange-listed public companies. However, he adds that ease of access to local geological information has historically proved to be a problem for explorers considering investing in the country. He says that this programme may simply add to the mountain of infor- mation that is inaccessible to the public.

Bristow says the CGS should be restructured and modernised. If the new mapping programme is to have any effect, he says, the CGS must come to terms with its “severe capacity shortage”, which is the result of years of underfunding and, hence, a shortage of experienced and skilled geologists to successfully drive the mapping programme.

Bristow suggests that the CGS actively collaborate with industry and universities to successfully complete the programme, noting that, while Mabuza claims to be working closely with universities on this initiative, he has not seen this come to fruition. He adds that mutually beneficial partnerships with companies, industry professionals and experts to share information and transfer skills are also lacking.

“Many excellent young geologists, mining engineers, hydrologists and geochemists, predominantly black, are unemployed; hence, the need to use them on a programme of this magnitude,” emphasises Bristow.

Baissac says that, with minimal greenfield exploration under way in the country and local mines ageing rapidly, government should focus its efforts on amending policies that have disincentivised mining in South Africa over the past 20 years, together with improving its geological information.

“It is not going to be enough to demonstrate the country’s exploration potential. Many African countries have excellent exploration potential, but they also struggle with bad governance and limiting policies, which cap exploration implementation.”

He points to a study completed by advisory services firm Eunomix last month, which shows that South African mining companies, compared with their competitors, have underperformed grossly as a result of policy compliance costs, onerous implementation requirements and restrictive policy.

Baissac and Bristow concur that the local mining sector should start to frankly address the challenges that threaten the industry. These include an ineffective and uncertain minerals policy, a dysfunctional DMR, inadequate education in the importance of geology, mining, related technologies and mineral resources at all levels of the education system, disinvestment, aggressive international competition for capital that leaves local mines uncompetitive, old orebodies, a lack of exploration, the absence of a junior sector and new projects and the replacement of depleted resources, vested interests and illegal mining, as well as grossly inadequate transformation and black ownership.

“While updating the country’s geological information is a great start, it will not make a difference to greenfield exploration in South Africa if it takes place in a silo . . . most of all, we need an enabling minerals policy that will encourage new investment, exploration and junior development and mining companies, which should be the engine room for reviving South Africa’s minerals industry. Sadly, the latest version of the Mining Charter and its host of unworkable requirements do not bode well for a sustainable revival of the industry,” concludes Bristow.

Edited by: Martin Zhuwakinyu

Creamer Media Senior Deputy Editor

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here