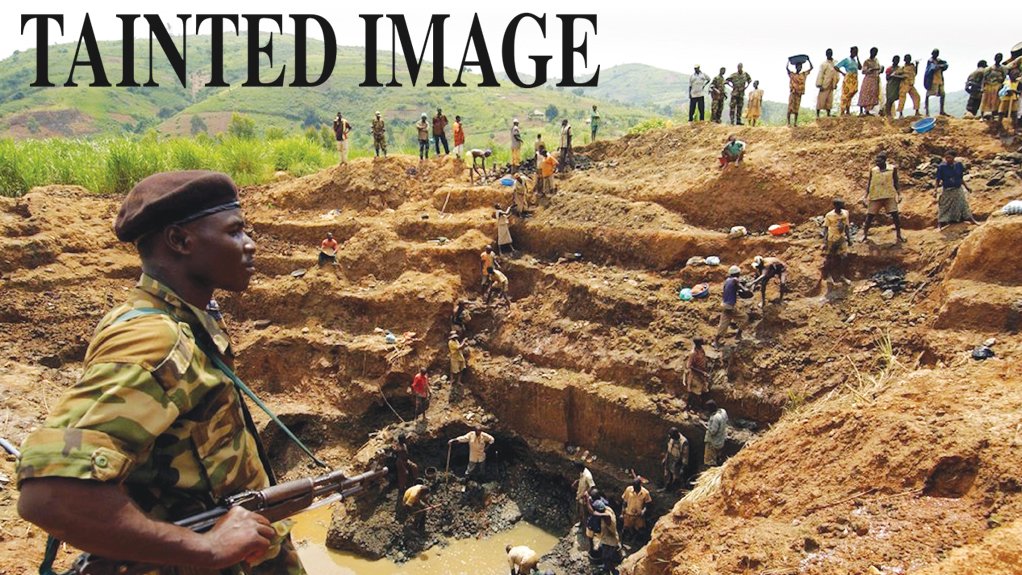

The diamond industry continues to be tainted by links between diamonds and human rights abuses, conflict finance and corruption.

This is according to international nongovernment organisation (NGO) Global Witness conflict resources campaign leader Michael Gibb, who notes that, although the diamond industry is not the only sector facing these threats, he believes it is unique in its particular “unwillingness and inability” to take genuine steps towards responsible business conduct.

“Diamonds are still linked to conflict and human rights abuses, and much more has still to be done to ensure that the profits are shared equitably throughout the supply chain,” he says.

He points out that Global Witness’s recent report on the conflict in the Central African Republic exposed widespread smuggling and links to conflict, and that its report on Zimbabwe’s diamonds documented hidden links that have funnelled significant diamond revenues to the partisan army and intelligence services.

“Both reports make it clear that the Kimberley Process (KP) – a [binding agreement] that prevents conflict diamonds from entering the mainstream rough diamond market – cannot alone deal with the full range of problems still prevalent in diamond supply chains.”

Gibb says companies must take far greater responsibility for the impact of their business activities and supply chains, and play a more active role in addressing them.

They can no longer simply pass this responsibility on to the limited KP Certification Scheme, which has often proven inadequate and incapable of the necessary reforms, he notes.

There has been considerable evolution in the willingness of companies – in sectors such as gold and 3T – to take individual responsibility for the impact of their businesses and the risks in their supply chains, mostly as a consequence of legislation, but some diamond companies are lagging behind, Gibb says.

“Diamond companies must acknowledge that they have an individual corporate responsibility to identify and deal with risks . . . in their supply chains.”

Further, a recent report by civil society watch dog Human Rights Watch says that the KP is narrowly focused on curbing the trade of diamonds that benefits armed groups, not abusive governments or their armed forces.

“It is not surprising that the KP has authorised exports of Zimbabwe diamonds, although they were – and continue to be – mined under highly abusive conditions,” the report notes.

It further states that governments have failed to create an independent monitoring system to check if the necessary customs controls are in place: “The KP applies to only rough diamonds, allowing stones that are fully or partially cut and polished to fall outside the scope of the initiative.

“Companies also have a responsibility to not contribute to human rights violations. To do this, they need to have due diligence safeguards in place to identify and respond to human rights risks throughout their supply chains.”

The organisation has found that many companies do not know where their gold and diamonds come from, and do not do enough to assess human rights risks.

In addition, jewellery and watch companies often publish limited information on how they address human rights risks in their supply chains.

WORLD DIAMOND COUNCIL

According to the World Diamond Council (WDC), however, the KP is undergoing a period of review, with the council driving meetings on the industry’s commitment to the KP and in various countries.

In March, at a United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) side event, the WDC discussed the KP and strategies to advance its ongoing contributions towards peace, security and sustainable development in diamond mining communities.

This year marks the beginning of a pivotal period for the KP – a two-year review and reform process led by the European Union chairmanship and ending during next year’s Indian chairmanship in 2019.

The WDC is the voice of industry for the KP and an official observer of the process.

“The KP is the first-ever minerals-based global mechanism to contribute to settling armed conflicts and has, over its relatively young life, significantly contributed to peace and security. In doing so, it has enabled the diamond industry to support and create employment, income and livelihoods for millions of people,” states WDC acting president Stephane Fischler.

However, the threat of instability and conflict remains and the KP’s work is not over.

“This important KP review period gives us the opportunity to address contemporary challenges facing the diamond industry and implement reforms to protect the human rights, freedoms and development of people who depend on the diamond trade,” he notes.

He has reaffirmed industry’s commitment to the KP, while also reinforcing areas for reform to ensure continued success.

“We want to broaden the scope of the KP to increase the likelihood of safe and secure working conditions, fair labour practices and sustainable development in diamond communities,” he says.

Fischler further states that the KP is a process for a reason – a tripartite with many participants, diverse points of view and numerous priorities.

“Even though only one group holds the power to enact change directly, we will not give up. Industry remains committed to working together with our partners to listen, discuss and reach consensus that drives positive change. I am especially encouraged by efforts of the Civil Society Coalition, now led and overwhelmingly represented by Africa-based NGOs, with whom we share a commitment to secure lasting change.”

SUPPLY CHAIN DUE DILIGENCE

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights make it clear that companies have a responsibility to ensure that they do not finance conflict or human rights abuses.

Supply chain due diligence is the internationally accepted way through which companies can meet this responsibility.

A practical standard has been developed by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, which covers diamonds and other mineral resources.

“This is not about restricting where companies source their diamonds; it is about how they do so. The simple five-step procedure takes companies through the process of identifying, managing and reporting on risk,” states Gibb.

It aims to ensure that supply chains work together to address problems, rather than sweeping them under the carpet or trying to deal with them in isolation.

“Ultimately, it is a way of changing what counts as business as usual, ensuring concern for those at the very bottom of the diamond supply chain is reflected in all facets of the business,” he notes.

Gibb advocates that the KP adopt a wider definition of conflict diamonds, establish an independent monitoring system and ensure more rigorous controls.

Jewellery companies, diamond traders, cutters and polishers need to establish robust human rights due diligence – and also need to require this from their suppliers – by doing thorough risk-based due diligence on supply chains, in line with international standards, he adds.

Gibb explains that this will enable companies to understand their supply chains better, get a sense of and deal with the risks in the supply chains from which they profit, and improve conditions in and along the ones on which they depend.

Through detailed public reporting on their efforts, they can also work more effectively with other companies in their supply chain, demonstrating to consumers, lenders, investors and regulators that they are responsible and transparent.

TECHNOLOGY

Gibb points out that there is a great deal of excitement around new technologies, such as blockchain, and any innovation that can assist in transparent and responsible diamond sourcing is, of course, to be welcomed, he says.

Earlier this year, Signet Jewellers announced that it would become the first retailer to join De Beers Group’s end-to-end diamond blockchain pilot programme, known as Tracr.

Tracr aims to complete the first digital link, from diamond production to retail, of diamonds. It is being developed by De Beers, with support from corporate investment and incubation firm BCG Digital Ventures and is expected to launch later this year.

A Signet project team will work alongside the Tracr team to ensure that the platform meets the needs of the jewellery manufacturing and retail sectors, with the partnership initially focusing on the tracking of diamond jewellery and expanding the pilot project’s scope to cater for smaller-sized goods.

“Tracr is focused on bringing the benefits of blockchain technology to the full diamond value chain – providing consumers with confidence, the trader with increased efficiency and lower costs, and lenders . . . with greater visibility,” De Beers CEO Bruce Cleaver said in a statement.

Signet Jewellers CEO Virginia Drosos comments that responsible sourcing of diamonds has always been an integral part of Signet’s corporate ethos, and this will be further strengthened through its cooperation with Tracr.

“We are joining the Tracr pilot because we believe that the project has strong potential to not only facilitate increased transparency and confidence in the industry but also foster much-needed digital transformation,” she says.

It is intended that a digital certificate, created by Tracr for each diamond registered on the platform and storing its key attributes and transactions, will enable retailers to provide consumers with confidence that the diamond is natural and conflict free, and has been tracked across the value chain.

De Beers announced in May that it had successfully tracked 100 high-value diamonds along the value chain on Tracr, marking the first time that a diamond’s journey has been digitally tracked from mine to retail.

However, Gibb says that, too often, new technology is captured to give further advantages to large companies and other powerful actors, further entrenching the vulnerability of artisanal mining communities and others unable to participate or access the technology.

Unlike the technological innovation in other sectors, it has not yet been accompanied in the diamond sector by the disruption required to challenge an entrenched business model in which human rights abuses and conflict financing are still too widespread.

“New technology and innovation can help companies do more and do better, but only once they have decided to change the way they do business by integrating genuine concern for those who comprise their supply chains throughout their business activities,” he concludes.

Edited by: Martin Zhuwakinyu

Creamer Media Senior Deputy Editor

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE

ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email subscriptions@creamermedia.co.za or click here

To advertise email advertising@creamermedia.co.za or click here